Authentication & Authorization Protocols Explained

Identity federation, basic authentication, LDAP, Kerberos, SAML, JWT, OpenID connect, OAuth, API Keys and RBAC explained

Introduction

Authentication is proving that you are who/what you say you are. authorization is proving that you have the permissions to access a resource. Both of these allow you to control who has access to your application and what they are allowed to do with that access.

To fully understand the difference, consider the following analogy. You need to be both authenticated and authorised in order to board a flight. Authentication is done with your passport, where it is checked to ensure the photo in your passport matches your face, to prove that you are who you say you are. After you have been authenticated, you need to prove that you have the permission to take a specific flight. This is done with your boarding pass.

Both authentication and authorization need to be carried out before you can board a flight.

When creating an application, you may want to have the ability to authenticate and authorise users so you can control access to your app. This article will explain the different authentication and authorization protocols and how they work.

Authentication protocols

Before we explore the different authentication protocols, a key concept must first be understood; identity federation.

Identity Federation

Identity federation is an important concept to understand, as it is the underlying principle behind many authentication protocols. Let’s break down what ‘identity’ and ‘federation’ mean.

Identity refers to unique pieces of information that represent a user within a system. It includes details that identify who the user is, such as a username, email, ID number, or other attributes that uniquely define the user. Here, a system could mean many things. For example:

Mobile or web applications - applications such as Gmail or Amazon require users to log in to manage their personal information

Corporate networks - Large organisations often have internal networks with various resources, such as databases, file servers, and collaboration tools. Employees log in to this network to access these resources, making the corporate network a "system" that relies on identity verification.

Federation refers to the collaboration between different systems to create a shared and trusted network that can be used to manage identities.

Identity federation is therefore a way for a users identity to be shared with a trusted network so that users can seamlessly access resources across different systems without needing to authenticate separately at each one.

The best example of this is when you use your Google or Facebook account to log into a mobile or web application, rather than creating a new account from scratch. The mobile/web application trusts your existing identity provider (Google or Facebook) to verify who you are, saving you from repeatedly signing up with different usernames and passwords.

Another example of identity federation is how your passport allows you to travel internationally. Other countries trust your home government's identity verification process. When you travel internationally, customs officials don't independently verify your citizenship from scratch. Instead, they rely on the passport issued by your government and trust that your government has done the job of verifying your identity. Similarly, identity federation enables systems to rely on verification done by trusted providers.

Basic Authentication

Basic authentication is a simple and antiquated method used to authenticate users.

Imagine a super exclusive restaurant that has a locked door. To get in, you need to provide the correct password. If the password is correct, you are allowed in, if its wrong, you are not permitted.

What could go wrong with this approach? Someone eavesdropping may be able to hear what your password is and then use that same password to gain access to the restaurant. Suddenly, access to this exclusive restaurant is not so exclusive.

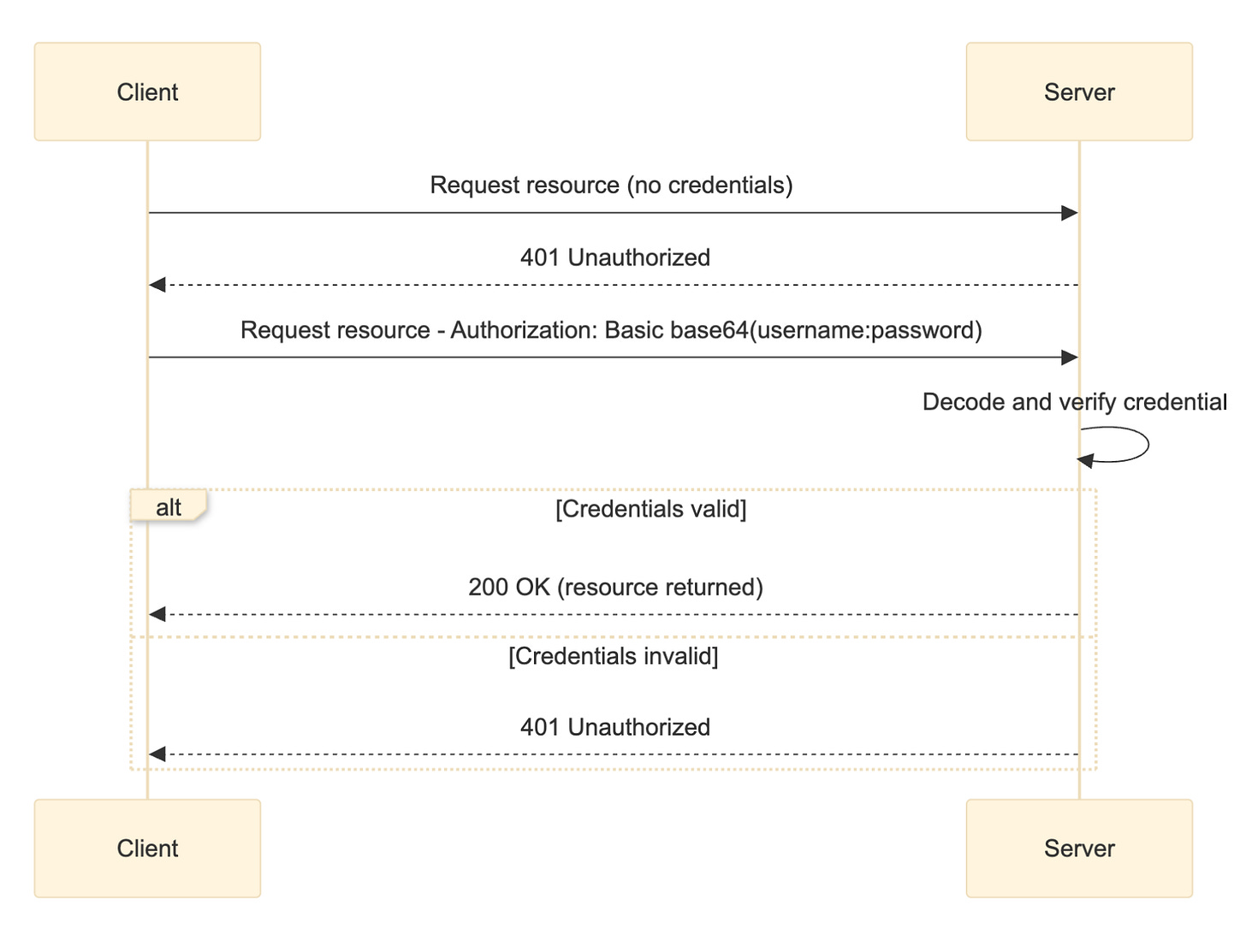

The sequence diagram below illustrates how basic authentication works.

With basic authentication, access to a resource is protected and your client (app or browser) has to send your username and password in the HTTP request header, encoded in base64 format.

Authorization: Basic <base64(username:password)>If your username is paul and password is squarepizza, paul:squarepizza is encoded to base64 and your authorization header becomes:

Authorization: Basic cGF1bDpzcXVhcmVwaXp6YQ==The server decodes the credentials back to the plaintext username and password and verifies these credentials against what is stored in a database. If the credentials are valid, the server responds by sending back the requested resource. If the credentials are invalid or missing, the server returns an HTTP 401 Unauthorized status, prompting the client to retry with valid credentials.

Today, basic authentication is rarely used in modern systems because it is not secure. With basic authentication, the credentials are sent with every request and are not encrypted. They are simply encoded, and attackers can intercept and decode the username and password.

LDAP (Lightweight Directory Access Protocol)

LDAP works like a guest list at a restaurant. Instead of providing a password at the door of the restaurant, the receptionist at the entrance has a list of approved guests. When you arrive, you give your name (username) and show ID (your password). The receptionist scans the guest list to see if you’re on it and checks your ID against the registered details. Only if you are listed and everything matches are you permitted entry.

So, how do you get your name on the guest list? The owner or operator of the restaurant needs to add your name to the list, this is the only way.

LDAP works in a similar fashion. It is essentially a protocol used to access and manage a directory. The LDAP administrator adds users to the directory and once there, they can log in and have access to some data available to them. Many enterprises use LDAP servers (e.g. Active Directory) to keep a master list of approved users and their passwords. When someone tries to log in, the application will check this directory via LDAP to see if the credentials match a known user and to fetch their details.

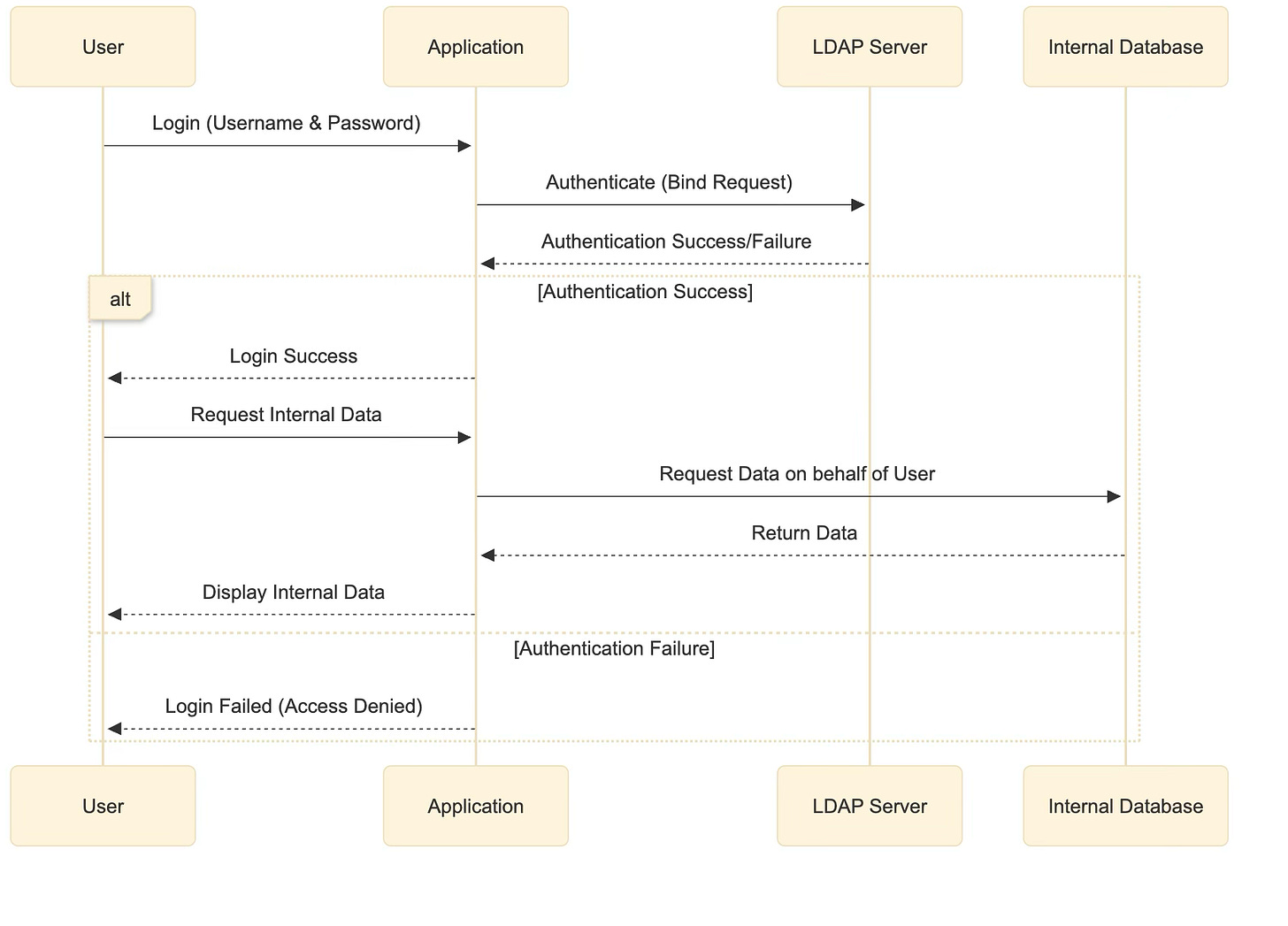

The sequence diagram below illustrates how LDAP works.

User sends login credentials to the Application.

The application verifies credentials with the LDAP server.

If successful, the user gains access and can request internal enterprise data. If failed, the application denies access.

Upon successful authentication, the application requests data from an internal service and delivers it to the user.

KERBEROS

Kerberos is a network authentication protocol designed to allow secure logins on untrusted networks by using tickets and a trusted third-party.

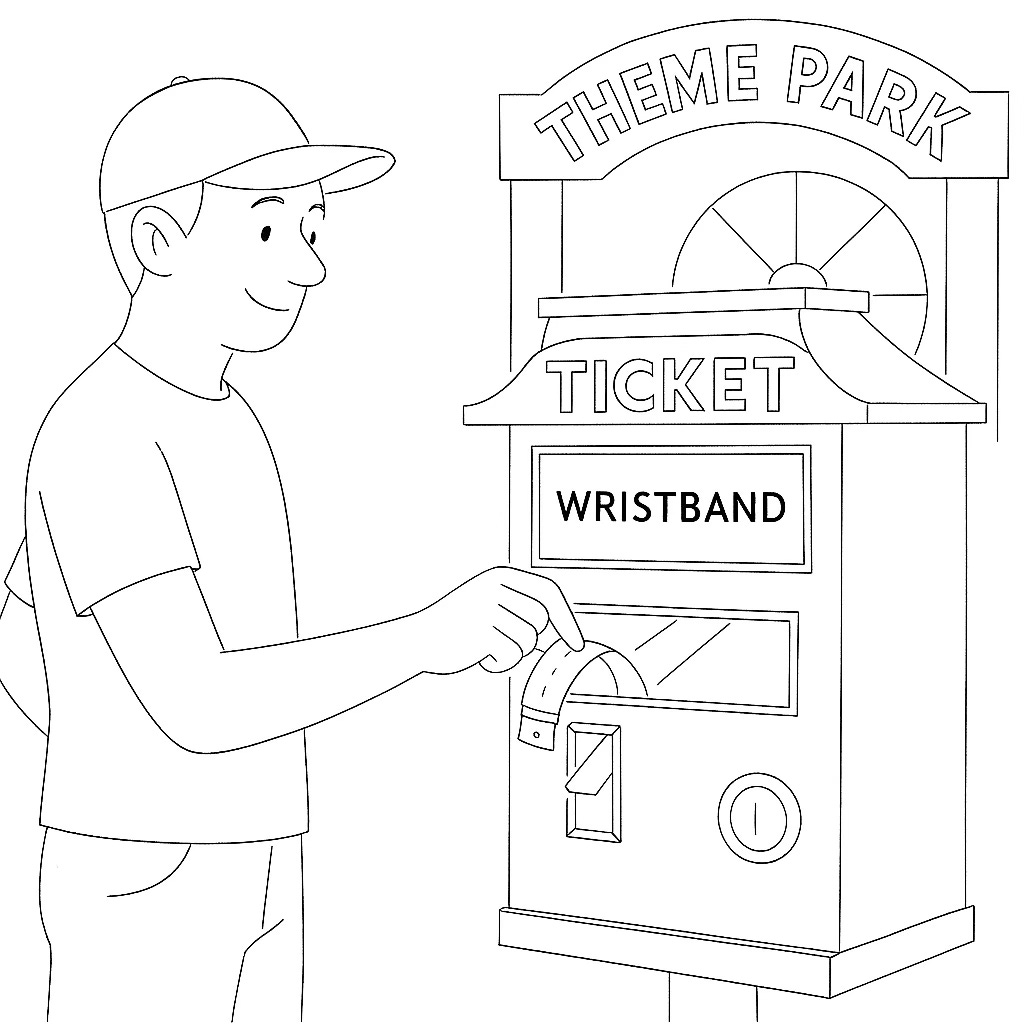

Imagine you arrive at a large, exciting theme park ready for a day full of rides. Before you can enjoy any rides, you need to verify your entry. At the park’s main entrance, there's no human attendant. Instead, there's a special ticket machine. You simply enter your purchase confirmation number (like the username and password you'd normally enter into your computer). After verifying your purchase number, the ticket machine prints out a special wristband for you to wear.

This wristband is important because it shows you've been checked and confirmed as an official park guest. With your wristband, you don't need to keep proving your identity or entering your purchase number repeatedly for the rest of the day.

Now, whenever you want to ride an attraction, let's say the rollercoaster, you first head over to the ride’s ticket booth. At the booth, you show your wristband. The booth attendant quickly checks your wristband, sees that you're verified, and prints a ride-specific ticket just for the rollercoaster.

Next, you walk to the rollercoaster entrance and hand the ride ticket to the operator. The operator checks your ticket, confirms it's valid, and lets you onto the ride.

After you are done with your ride, you head to the food court and again show your wristband in exchange for a ticket that allows you entry to the food court.

Notice that throughout this process, you never had to re-enter your purchase number or show any form of ID; the wristband grants you tickets and the tickets grant you entry to different parts of the park.

This is similar to how Kerberos authentication works. You initially log in once (entering your purchase number for the theme park), receive a Ticket Granting Ticket (the wristband), then request specific tickets for each service (ride tickets, food court etc), which the service providers validate before granting you access.

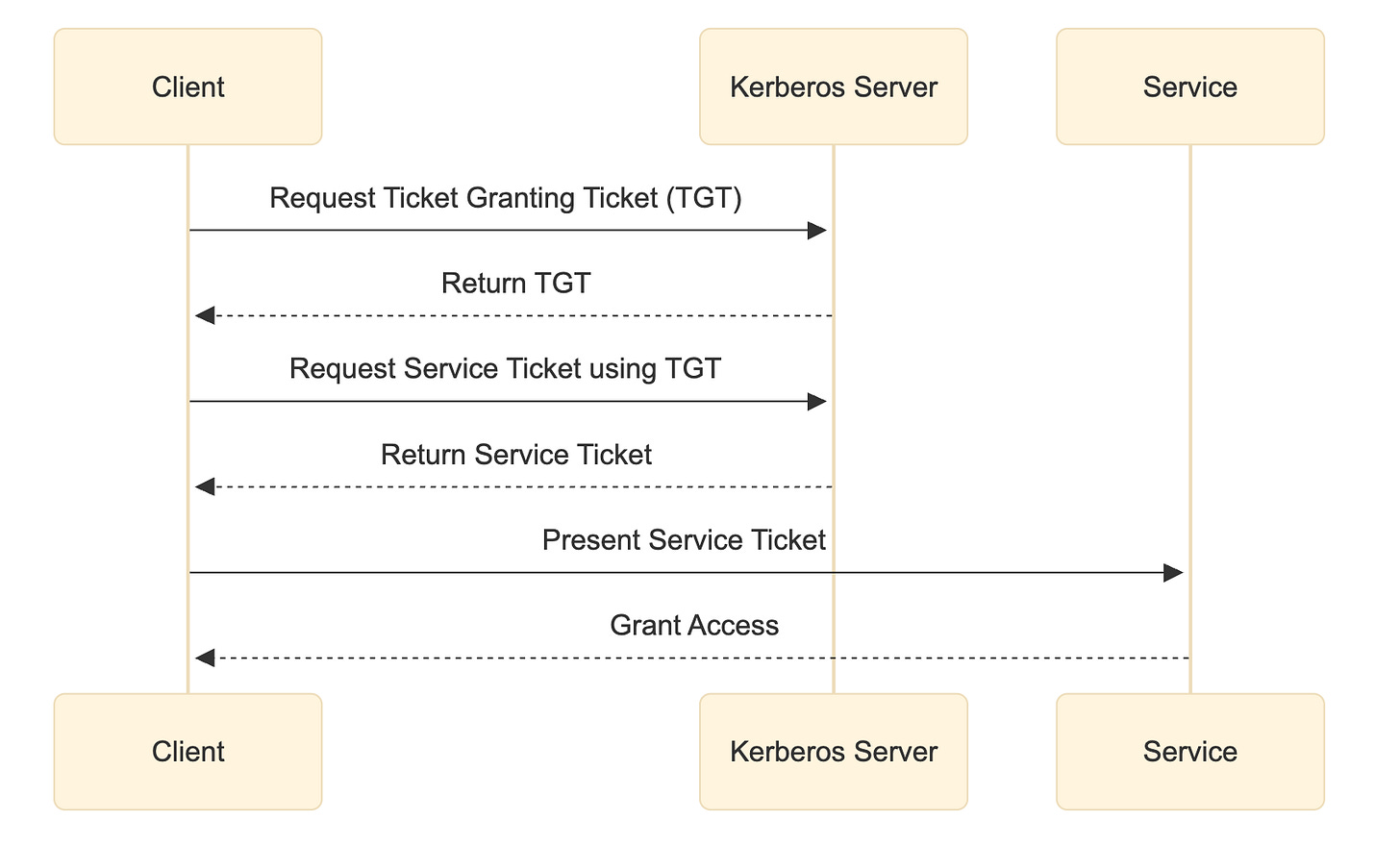

This is illustrated in the sequence diagram below.

Client asks the Kerberos Server for a TGT (ticket granting ticket) i.e. the initial ticket

With that TGT, the client requests a service-specific ticket

Client presents the service ticket to the service, which grants access

SAML (Security Assertion Markup Language)

SAML is an XML-based open standard for exchanging authentication and authorization data between parties, primarily used for Single Sign-On (SSO) in web and enterprise applications.

SAML is a form of identity federation. Recall that Identity federation is a way for a user’s identity to be shared with a trusted network so that users can seamlessly access resources across different systems without needing to authenticate separately at each one.

Going back to the restaurant analogy, imagine an exclusive restaurant that only allows people to enter if they are on the guest list. But there is a catch. If your name is not on the guest list, you still have a chance of entering the restaurant, but you need a letter of invitation from someone else that the restaurant trusts, so maybe the owner of this restaurant, an existing guest of the restaurant or another similarly exclusive restaurant.

Instead of the normal ID check at the door, you present a signed letter from a known identity, let’s assume the restaurant’s owner, that says “This is John, and I certify he is who he says and he should be given access to the event.” The restaurant’s door staff trust the letter because it’s stamped and signed by a known authority (they might even have a list of acceptable authorities). Upon seeing it, they let you in. In this way, you didn’t have to personally prove your identity to the club; the letter from the owner of the restaurant did that for you. Similarly, with SAML, your identity provider “writes a letter” (the SAML assertion) to the service you want to access, saying “This user is authenticated and here are their details,” and the service lets you in based on that.

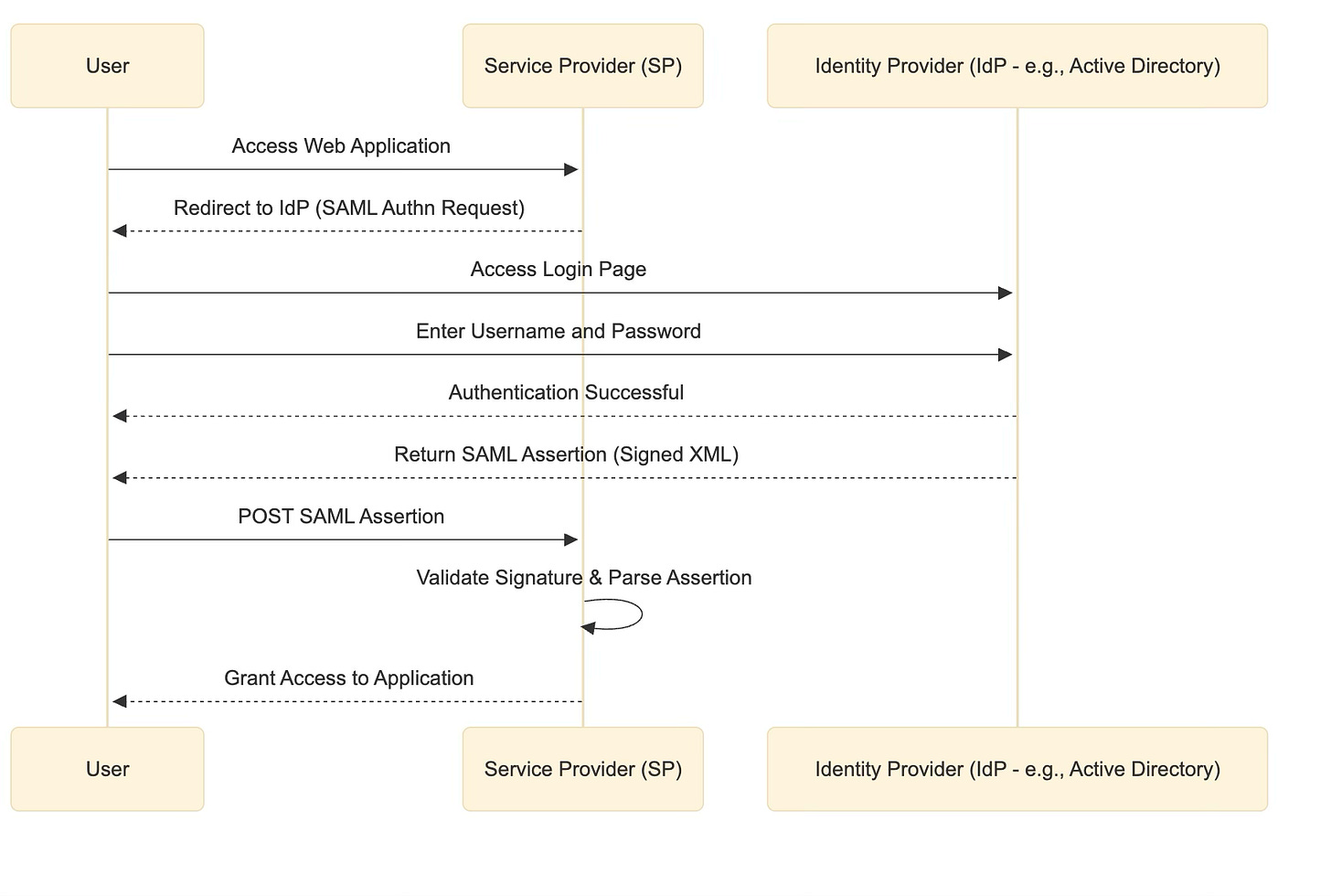

The sequence diagram below illustrates how SAML works.

SAML enables an Identity Provider (IdP) such as a company's central login system, Microsoft Active Directory for example, to confirm your identity to another Service Provider (SP), like a third-party web application.

When you try to access the web application, you're redirected to your company's identity provider, usually through a login page. Once you successfully log in, the identity provider generates a digital confirmation called a SAML assertion (an XML document). This assertion includes information about you, such as your username or assigned roles, and is digitally signed by the identity provider.

The signed assertion is then sent to the Service Provider, which verifies the digital signature. After validation, the Service Provider grants you access without needing you to enter your password again.

In short, SAML securely establishes trust between different systems by allowing one domain (the identity provider) to authenticate users for another domain (the service provider) using digitally signed tokens.

OpenID Connect (OIDC)

OpenID Connect is a modern authentication protocol often used for federated identity and “social login” and is typically used by modern mobile and web applications. Technically, it’s an authentication layer built on top of OAuth 2.0 (an authorization protocol that will be covered later). OAuth 2.0 was designed for authorization, not authentication, but people often misused it to get user identity. OIDC was created to fill that gap using OAuth 2.0’s mechanics (REST, tokens etc.) but standardises how to get user identity information in the form of an ID Token.

OIDC is another federated authentication protocol, similar in many ways to SAML. Just like SAML, OIDC lets users authenticate with a trusted third-party Identity Provider (IdP) and then access other applications without re-entering passwords.

The difference between the two is the lower level implementation details. For example, OIDC uses JSON web tokens (JWTs) while SAML uses XML based assertions.

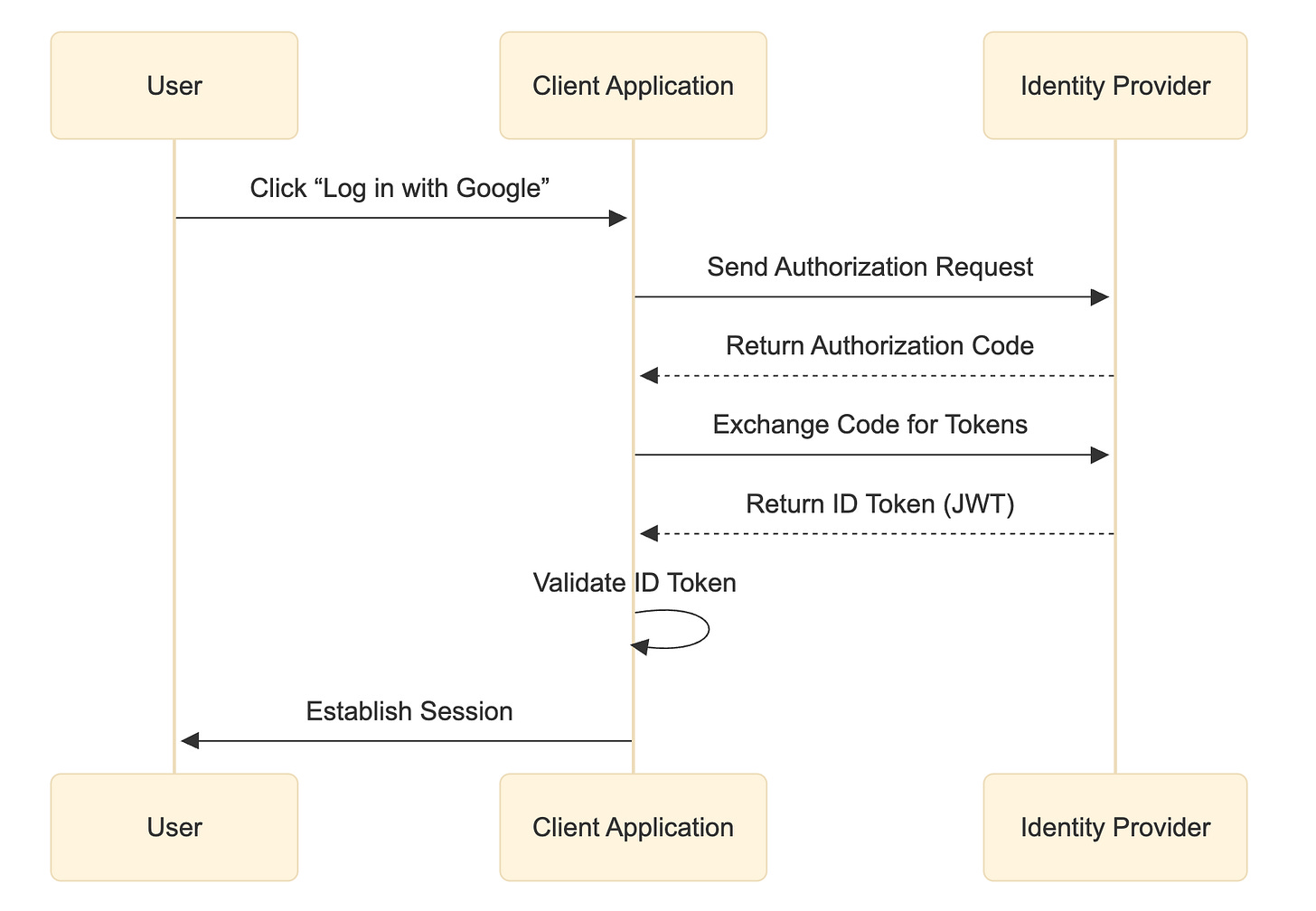

The sequence diagram below explains how OIDC works.

In an OIDC flow, a user tries to log in to a client app, the app redirects them to an OpenID Provider, which is an OAuth 2.0 Authorization Server that supports OIDC, for example Google, Facebook, or a corporate IdP supporting OIDC. The user authenticates there, using their Google or Facebook credentials, and, if successful, the Identity Provider sends back an Authorization code which is then exchanged for ID Token (a JSON Web Token called a JWT) to the client that contains the user’s identity information. The client application can then verify the ID Token’s signature (to ensure it’s from a trusted provider) and log the user in, knowing their identity has been confirmed by the provider.

Authorization Protocols

OAuth 2.0

OAuth 2.0 is the latest version that builds upon the original OAuth framework, making it simpler and more secure.

OAuth 2.0 is an authorization framework widely used to allow one service to access resources on another service on behalf of a user, without exposing the user’s credentials. In simpler terms, OAuth 2.0 lets you grant a third-party application limited access to your data from another service. It does so by issuing access tokens to the third-party app after you approve a request.

How is this related to OIDC? OAuth 2.0 answers: “Can this app access this resource?” while OIDC answers: “Who is the user?”

OIDC reuses OAuth 2.0’s flow and adds a standardised way to prove user identity.

OAuth 2.0 is like visiting a secure office building where you sign in at the front desk. Instead of being given the master keys to the entire building, the receptionist issues you a temporary visitor badge after an employee in the building (a trusted identity) approves your visit. That badge lets you access only specific floors or rooms and only for a limited time. You never see the employee’s personal access codes, and once your visit ends, the badge stops working. In the same way, OAuth 2.0 gives a third-party application a temporary, limited-access token to act on your behalf without exposing your login credentials.

API Keys

An API key is a simple way for a system to identify who is making a request to an API. When your application sends a request, it includes its API key, and the server uses that key to recognize the caller, apply usage limits, and decide whether the request is allowed. API keys are mainly used for identification and basic access control, not for proving a user’s identity or granting fine-grained permissions. Because of that, they’re usually kept secret and used in server-to-server communication. Exposing an API key is dangerous because anyone who obtains it can use the API as if they were you.

An API key is like a shared Wi-Fi password for a café. If you know the password, you can get on the network and use the internet, and the café can track overall usage or cut access if the password is abused. But the password doesn’t prove who you are personally, and it doesn’t restrict what websites you can visit. It just says, “someone with this password is allowed in.” If the password gets leaked, anyone can use it until it’s changed.

RBAC

Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) works by assigning roles to users and permissions to roles, instead of giving permissions directly to each user. A user might be assigned a role like Admin, Editor, or Viewer, and each role comes with a predefined set of actions they’re allowed to perform, such as reading data, updating records, or managing users. When a user tries to perform an action, the system checks their role and allows or denies the action based on the permissions tied to that role. This makes access management easier, more consistent, and more secure, especially as systems grow.