AWS IAM (Identity and Access Management) Explained

Users, groups, roles & policies

Summary

AWS IAM (Identity and Access Management) provides control over who can access your AWS services and resources based on some predefined permissions. The two keywords here are “who” and “permissions”. “Who” refers to a specific identity, this can be a user, group or role while “permissions” refer to the policies that are attached to an identity. These permissions either allow or deny access to a resource.

IAM is the AWS way of authenticating and authorising identities. Authentication is not, however, the same as authorisation. Authentication is concerned with the “who” while authorisation is concerned with the “permissions”.

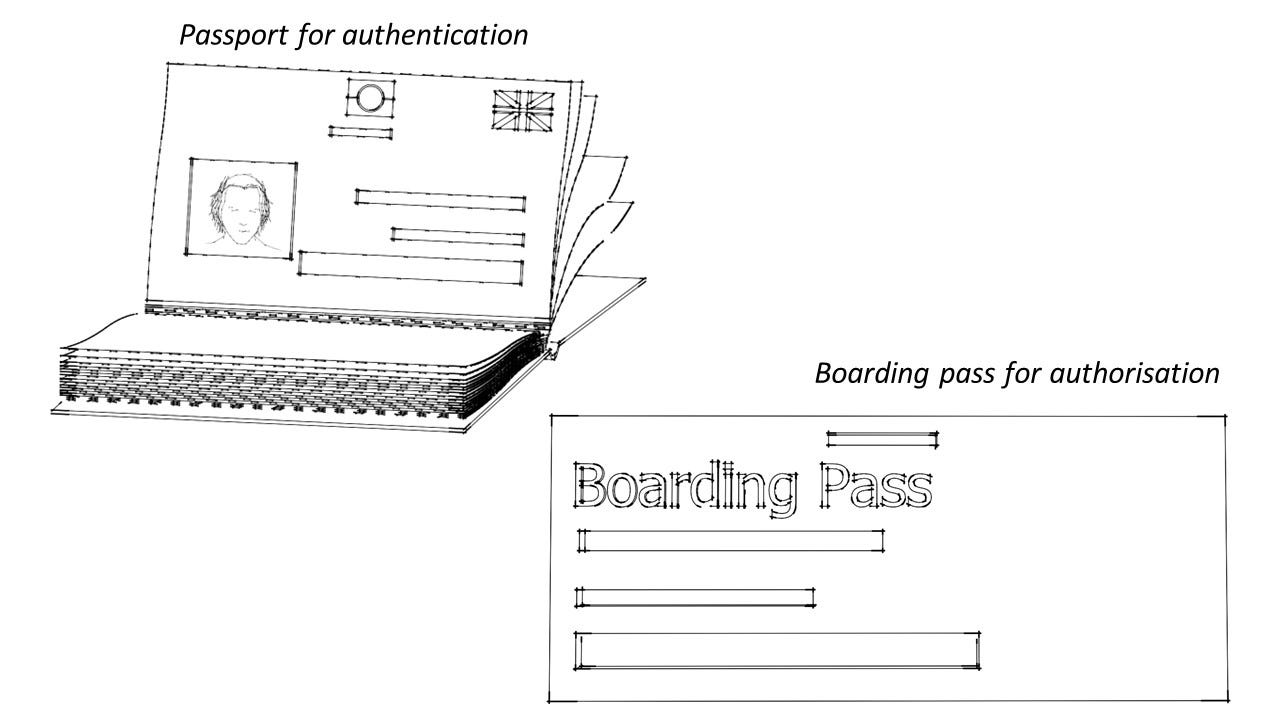

Authentication is when an identity proves it is what/who it says it is while authorisation is proving that you have the permissions to access a resource. To fully understand the difference, consider the following analogy. You need to be both authenticated and authorised in order to board a flight. Authentication is done with your passport, where it is checked to ensure the photo in your passport matches your face, in order to prove that you are who you say you are. After you have been authenticated, you need to prove that you have the permission to take a specific flight. This is done with your boarding pass. Both authentication and authorisation need to be carried out before you can board a flight. Similarly, both need to be carried out before you can access AWS resources.

IAM users, groups and roles are concerned with authentication - proving that you are who you say you are. They are like passports that get you through security in an airport. Without a boarding pass however, you cannot board a plane. The IAM policy is like a boarding pass, in that it grants or denies access to specific resources.

IAM Users

This is any identity (humans or an application) that requires long term access to AWS resources. These entities make requests to IAM to get authenticated before any interaction with AWS resources is allowed the happen. Authentication is done using a username/password combination for humans accessing AWS through the console or through access keys for an application or a human accessing AWS through the command line interface.

IAM Groups

IAM users can be placed in an IAM group. IAM groups makes it easier to organise a large number IAM users and apply permissions on a group level instead of an individual level because the latter does not scale for a large number of users. Imagine you have a team that consists of developers, architects, admin staff, DevOps engineers, live support and testers. Each of these teams have 10 people each, for a total of 60 people. Instead of setting permission policies for 60 people individually, you can put IAM users into their respective groups and apply permissions on a group level. This makes it easier to organise permissions and also easier to scale as your team grows.

There are no login credentials for IAM groups. Also, a user can belong to multiple groups, so for example, an IAM user that is in the DevOps group can also be in the live support group. This maps neatly to the real world where a DevOps engineer can also be in live support.

IAM Roles

IAM roles are used to grant temporary access to multiple identities. These identities could be humans external to AWS accessing your services, IAM users or applications. These identities assume the role temporarily, and any permission policies attached to the role are by proxy applied to the identity assuming that role. IAM roles are important because AWS has hard limits on the number of IAM users (currently 5000).

IAM policies that are attached to roles come in two flavours - trust policy and permission policy.

The trust policy controls which identity (e.g. IAM users, AWS resources like EC2 instances, anonymous entities) can assume that role. Once a role is assumed by an identity, AWS issues it Temporary Security Credentials. You can think of the trust policy as how AWS authenticates an IAM role to ensure that only the identity that is allowed to assume the role can assume the role i.e. that an identity has proved that it is who/what it says it is. However, there is a catch. With trust policies, this authentication only works for a period of time, so once that time has elapsed, the identity needs to re-authenticate and get new Temporary Security Credentials.

The permission policy is relatively straightforward - it defines the permissions that the role has, which, by proxy, defines the permissions that the identity assuming that role will have.

IAM roles are a relatively difficult concept to grasp, so if you don’t quite understand it yet, please read on and it will become clearer.

IAM Policy

IAM Policies are attached to identities, so users, groups or roles. IAM policies can also be attached to some AWS resources. These types of policies are called resource based policies.

IAM policies are JSON documents, consisting of one or more statements that grants or denies access to AWS resources.

The IAM policy below shows how permissions are granted to an identity to read and write from an S3 bucket.

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Sid": "ListObjectsInBucket",

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": ["s3:ListBucket"],

"Resource": ["arn:aws:s3:::bucket-name"]

},

{

"Sid": "AllObjectActions",

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": "s3:*Object",

"Resource": ["arn:aws:s3:::bucket-name/*"]

}

]

}Sid - optional field that lets the reader quickly identify what a statement does.

Effect - allow or deny

Action - what action are you trying to perform. Format is service:operation

Resource - which resource are you interacting with. Typically use ARN (Amazon Resource Name) which uniquely identify AWS resources.

By default, all requests are implicitly denied unless a policy explicitly has an “allow” as is the case in the example above.

Bringing it All Together

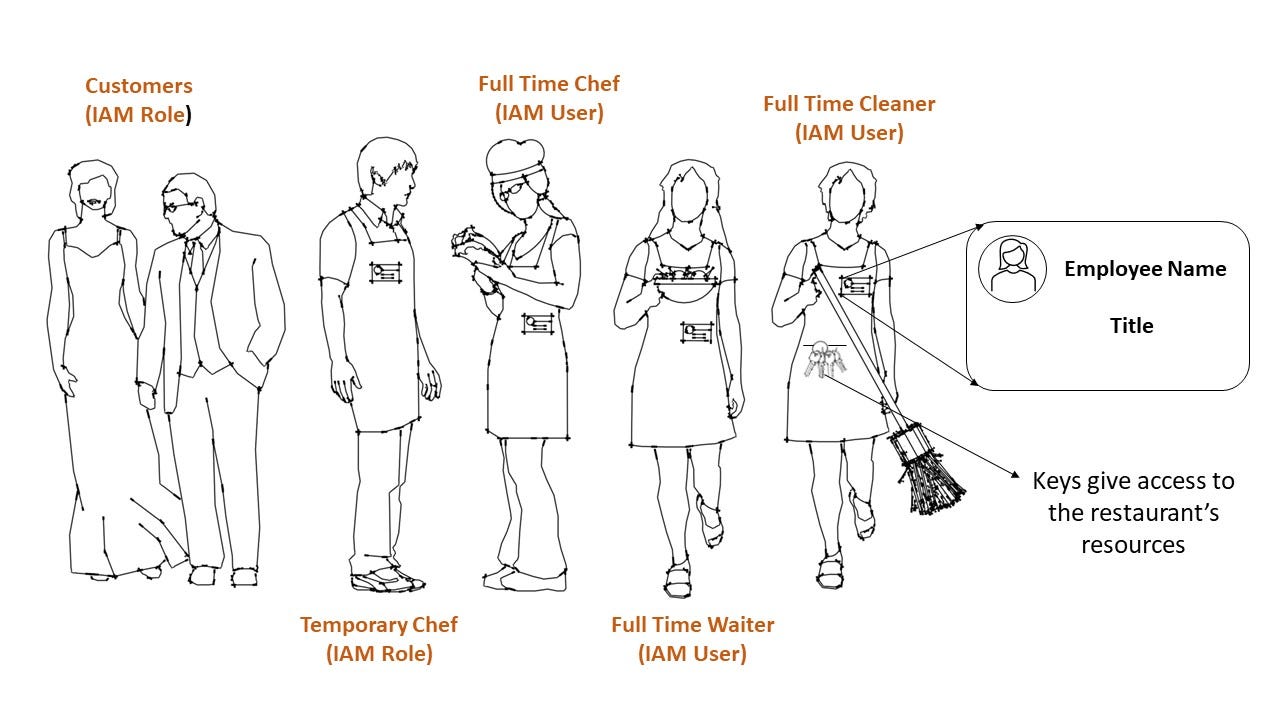

Consider a pizza restaurant. It will have some full time employees - chefs, waiters and cleaners. It may also have some part time chefs to help during peak demand on evenings and weekends. If the restaurant is any good, it will also have customers who can eat in and take out.

To draw an analogy with AWS IAM, the full time employees are like IAM users. They require long term access to the restaurant’s resources as shown above. These users will all belong to different groups - the waiters, chef and cleaners group i.e. all waiters for example will have the same job title of “waiter”.

How are the restaurant’s employees authenticated? How do we know that they are who they say they are? Name badges with a picture will do the job. This can also show their title which is analogous to the IAM group that they belong to.

The permission policies that define what resources the restaurant’s employees can access are applied on the group level, since every waiter, chef and cleaner will have the same permissions. This may not be true in reality, as the head chef for example may have privileged access. But for simplicity, lets assume it is true.

How does the restaurant manager control who has access to what resources? Doors with locks will do just fine. Keys act as a policy as they control access to parts of the restaurant. An identical set will be given to all waiters, since waiters will need the same level of access to the food/drink storage room, kitchen and seating area.

The same logic will apply to the other full time employees, where the appropriate set of keys are handed out so that they can use the restaurant’s resources as needed. Giving keys to the restaurant employees is analogous to attaching a policy to an IAM user or group. Without the keys, the employees cannot access parts of the restaurant. Similarly in AWS, without policies that explicitly allow an action, requests cannot be made to AWS resources. The default state in both AWS and our restaurant analogy is an implicit deny when trying to access resources.

The part time employees, like a temporary chef for example, and the customers, don’t need long term access to resources but will need short term access, analogous to IAM roles.

The part time employees can only work during a short window - say during evenings on the weekend. Outside of this time, they don’t have permissions to use the restaurant’s resources. This part time chef does not have to be the same person. It could be a different person every week, unlike the full time employees that have specific identities. A part time chef will therefore assume the role of a chef and get a temporary badge that he keeps for the duration of his shift, analogous to an entity assuming an IAM role that has a policy attached to it and getting Temporary Security Credentials that will expire after some time. Again, the policy here is the set of keys that grant permission to parts of the restaurant while the Temporary Security Credential is the temporary badge used to authenticate the chef.

Similarly, the customers are analogous to IAM roles for two reasons. First, they only require temporary access to the restaurant. Second, and perhaps more importantly, a successful restaurant will have tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of unique customers over its lifetime. Having a large number of unidentified entities is a perfect use case for IAM roles. Recall that with AWS, there is a hard limit of 5000 for the number of IAM users you can have. If there is a use case where the number of IAM users required will exceed this 5000 limit, using IAM roles is your only option around this.

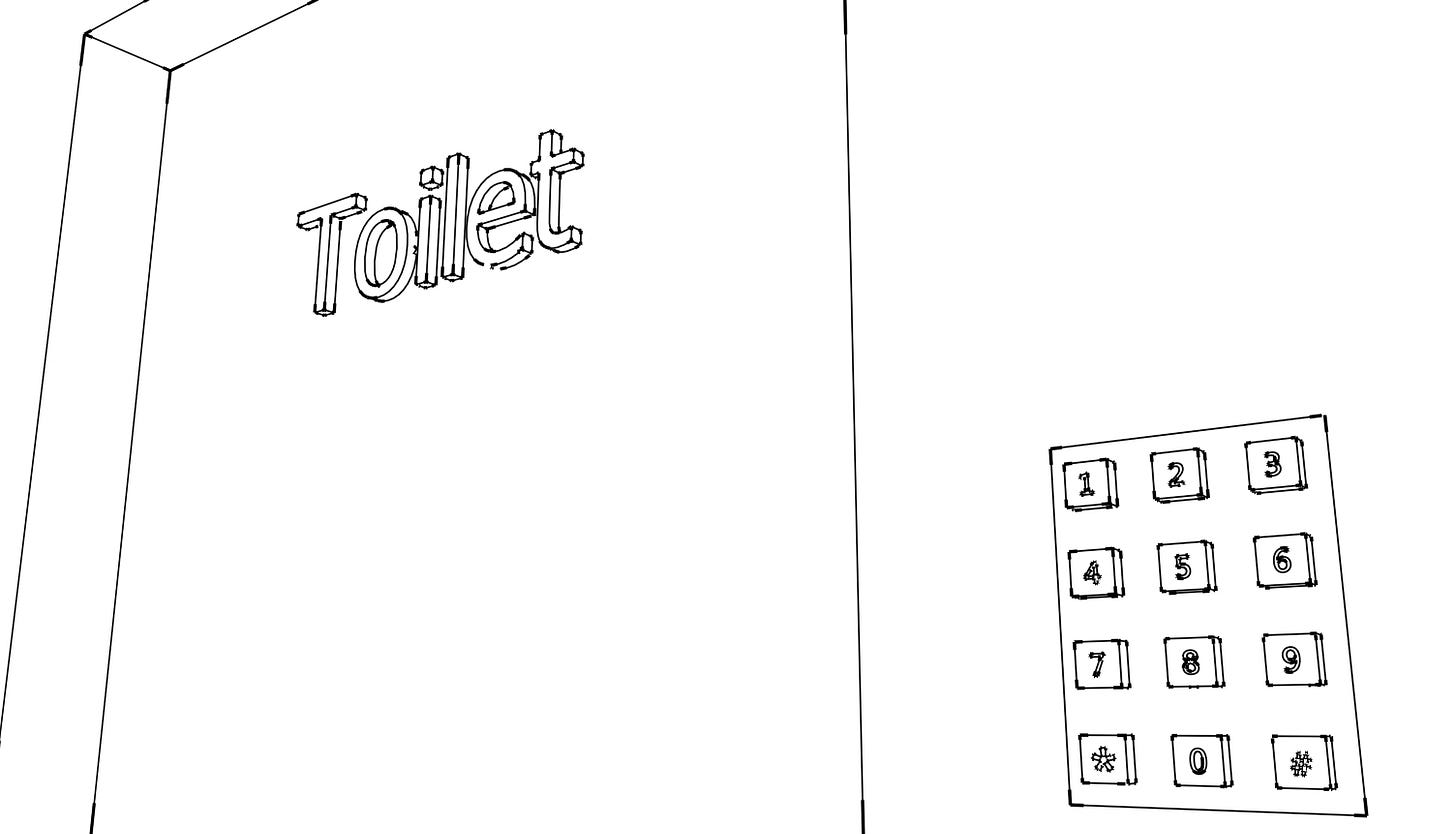

Just like how IAM roles are assumed, the customer first needs to order something to prove that he/she is a customer and can assume the role of a customer. After the customer role is assumed, the permissions policy attached to the customer role is then applied to the customer as well. Customers have permissions to only use some resources like the seating area and the toilet. To keep the analogy realistic, access to the toilet is controlled by entering a passcode which changes everyday thus ensuring that the access is temporary. This passcode is analogous to the policy attached to the customer role that grants temporary access to the toilet.

Example Use Case of IAM Roles

Consider the following very simple architecture - an EC2 instance running an application that needs full access to an S3 bucket. How would you give the EC2 instance the permission to read and write objects from an S3 bucket? This is explained in the diagram below.

Create an IAM role for your EC2 instance

Attach an IAM policy to the role that gives full access to the S3 bucket

Let the EC2 instance assume the role

The IAM policy for full S3 access mentioned in step #2 is:

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": [

"s3:*",

"s3-object-lambda:*"

],

"Resource": "*"

}

]

}

You can now read from and write to the S3 bucket. Notice that in the policy above, it doesn’t specify any ARN, but just says “*” for the resource, which means all S3 buckets. If that is what you want then this policy is fine. If however you want to specify a single bucket then you need to give the bucket ARN.

Although a somewhat boring topic (compared to other topics that will be covered in this newsletter), understanding IAM and the difference between users, roles, groups and how policies work gives a strong foundation on which to architect and build secure solutions with AWS.